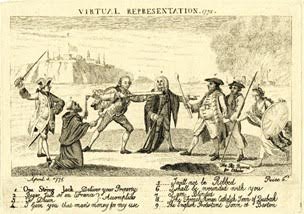

Before the charters, however, no independent governance or separation from the mother country was broached until those seeking religious freedom fled Britain to escape persecution. The only declarations were Lawes Divine, Morall and Martiall issued by the Virginia governor in 1610 and 1611 on the approval of London Virginia Company. They were the earliest extant English-language body of laws, but the laws only regulated conduct and did not provide for jury trials even though colonists were entitled to the “rights of Englishmen.” In fact, no legislature created the laws, and there was no court to enforce them. The Mayflower Compact in 1620 identified those seeking refuge in the New World as “Separatist” established early on they were severing ties with England—sort of. The first governing document setting forth the framework of Plymouth Colony was written by separatist Congregationalists who called themselves "Saints.” Later they were referred to as Pilgrims or Pilgrim Fathers. They were fleeing from religious persecution by King James of England. Haueing vndertaken, for ye glorie of God, and aduancemente of ye christian ^faith and honour of our king & countrie, a voyage to plant ye first colonie in ye Northerne parts of Virginia· The 41 signers of the compact while establishing themselves as separatist said they were planting a colony, which can be interpreted as an extension of the English realm leading to the duality of the settlers’ “nationalism” and loyalty to Britain. The adoption of English common law by colonists is outlined in a document discovered in Charlton, Georgia in State v. Campbell (1801). The remark states “When the American Colonies were first settled by our ancestors it was held, as well by the settlers…that they brought hither as a birthright and inheritance so much of the common law as was applicable to local situation, and change of circumstances.” British loyalists took refuge in the prestige of authority, of the venerable power which time and custom seemed to sanctify. They appealed to the loyalty of being an English subject. Warning of the dangers that came with innovation and modernity, Loyalists denounced the ambition of the patriot leaders and reminded the people of the power of Great Britain -- a power to save or to destroy. Additionally, “…English subjects, as the law is the birthright of every subject, so wherever they go they carry their laws with them, therefore, such new-found country is governed by the laws of England….” The strongest legal bonds between England and the American colonies lay in the colonial charters, many of which guaranteed residents in the colonies would eventually become “Our Loving subjects and live under Our Allegiance.” Ambiguity, however, in the colonial charters created uncertainty as to whether the authority to naturalize alien resident colonists resided within the colonies themselves or emanated directly from Parliament in London. Legislative bodies from both locations ultimately issued separate and sometimes conflicting naturalization laws, the interaction of which influenced early patterns of non-English immigration to the American colonies, and ultimately fomenting the impulse to seek independence from England. The peculiarities of emigration involving laws, citizenship, autonomy, social justice, civil rights and independence created contrariety and uncertainty among the colonies towards England —not dissimilar from some countries currently dealing with immigrants, refugees and displaced persons seeking asylum for a variety of reasons. “English common law was less clear on the status of alien residents in the colonies, who generally faced a difficult naturalization process to obtain the same legal rights inherent to natural-born English and their descendants. Issues in early naturalization policy stemmed from the legal relationships between England and its colonies,” according to James H. Kettner in “The Development of American Citizenship (1608-1870). “Taxation without Representation” was the cry and the culmination of years of discontent and alienation of colonists. And as stated in Part I, British resources were being stretched and new sources of revenue were needed. The Stamp Act of 1765 was a tax on paper for all American colonists and required them to pay a tax on every piece of printed paper they used. Ship's papers, legal documents, licenses, newspapers, other publications, and even playing cards were taxed. Granted the tax was destined to protect and defend the American Frontier; still, colonists were not involved in the decision.  Virtual representation Virtual representation Did the colonists really want to be represented in English the parliament, or were equality and sovereignty leading the charge for liberty? Colonists were not satisfied with what was called “virtual representation” that fanned the flames of discontent. This type of representation cited by the members of parliament, including the Lords and Crown in Parliament, was the right to speak for the interests of all British subjects, no matter where they lived. Considering the oddness and unequal application of the naturalization processes, representation might not have included all colonists, which contributed to discontent. The First Continental Congress in the colonies sent an olive branch petition to parliament requesting representation. Parliament replied that virtual representation was the only option, and the colonies rejected the premise. Revolt was inevitable. The American Revolution reflected an emerging philosophy that human beings are not only intellectually in charge of their own lives and future personally, but also the creators of laws governing their persons, property and country. The Declaration of Independence opens with an explanation of the desire for sovereignty by dissolving “the Political Bonds [England] which have connected them,” furthermore demanding, “separate and equal Station to which the Laws of Nature and Nature’s God entitle them.” The American Revolution was the political consequence of systemic inequality and oppression writ large in the colonies with roots going back to the first settlers. The French political thinker and historian Alexis de Tocqueville writes in “Democracy in America,” “Equality will find its way.” Furthermore, “To conceive of men remaining forever unequal…is impossible; they must come in the end to be equal upon all.” As Americans observe this 4th of July, we celebrate advancing culturally towards equality in many ways, but economic inequality remains one of the chief challenges of this century. Most Americans income growth was only 3.3 percent since 2013, while the richest 1 percent grew by 10.8 percent. By 2014, families recovered only 40 percent of what they lost during the Great Recession. Tocqueville’s prophecy that equality finds its way reaches out to the 21st century, for Americans will be seeking pathfinders now and in a future who lead with intention and dignity towards prosperity and equality for all. Resources Scholarship law History Illinois Mayflower history History Think Progress “Democracy In America,” by Alexis de Tocqueville. Penguin Books Limited 1956, pg. 54-56.

5 Comments

eileen

4/7/2015 03:20:17 am

Thanks for an interesting July 4th post and I hope you enjoy your celebratory weekend :)

Reply

Dava Castillo

4/7/2015 10:42:11 am

Thank you for reading commenting Eileen.

Reply

Eileen

4/7/2015 12:30:51 pm

And why not!!

Reply

Dava Castillo

4/7/2015 07:05:39 pm

Thank you Eileen! Leave a Reply. |

Dava Castillo

is retired and lives in Clearlake, California. She has three grown

children and one grandson and a Bachelor’s degree in Health Services

Administration from St. Mary’s College in Moraga California. On the

home front Dava enjoys time with her family, reading, gardening, cooking

and sewing. Archives

November 2015

|